Apple USB C Earpods

Apple USB C Earpods

Ok, hear me out: what if …

Ok, hear me out: what if …

There have been moments where having HTTP/2 on localhost would have been handy. Over the years I have tried a few things and recently I found a way I liked. I tend to dislike having to install too many things, but for this, it seems impossible to avoid. My instructions are based on macOS Catalina (10.15) (for Safari), but should work for previous versions and future versions as well.

My steps were:

From the Terminal app, generate a self-signed certificate to use for SSL. (maybe change to the directory you’d like to store the certs in first?, in my case “/Users/oelna/.certificates”)

openssl req -x509 -nodes -newkey rsa:2048 -keyout key.pem -out cert.pemThis will create two .pem files (without setting a password for the key, which I found invaluable on a local machine, since I don’t want to enter a password every time I start the server.)

During creation I chose to put in some reasonable values for country name, organization name and common name (“localhost.”).

I tried to figure out a way to do this with the Python built-in HTTP server, but couldn’t, so I begrudgingly installed twisted for Python 3.

pip3 install twistedDepending on where you saved the .pem files generated earlier, you may have to adjust the paths for them in the following start command for twisted:

twistd -n web --path=. -c /Users/oelna/.certificates/cert.pem -k /Users/oelna/.certificates/key.pem --https=4433The parameters are pretty self-explanatory: -c is the certificate location, -k is the key file location, –https is the port the server will listen on, and –path is your website root (Most of the time I run the command from the directory the files are in, so I just put . there (=current directory)

Twisted should start up and if it doesn’t fail, your site is ready for you at https://localhost:4433

Safari will complain, when you load the page, but you can click your way through.

Chrome is a completely different beast, though, and I have needed to make a few changes to how the certificates are created.

Chrome

The instructions above worked well for me, but for Chrome I needed to go about it a little differently (sadly, more complicated). For this I used the instructions on Stackoverflow.

You need to become your own CA (“certificate authority”) and trust it on your machine. This fake CA will issue a certificate for localhost (which has to include something called subjectAltName). The resulting certificate for localhost also needs to be imported to Keychain and trusted for use with SSL. Let’s do it!

# generate the CA key and cert

openssl genrsa -des3 -out myCA.key 2048

openssl req -x509 -new -nodes -key myCA.key -sha256 -days 825 -out myCA.pemPrepare this localhost.ext file beforehand:

authorityKeyIdentifier=keyid,issuer

basicConstraints=CA:FALSE

extendedKeyUsage=serverAuth,clientAuth

keyUsage = digitalSignature, nonRepudiation, keyEncipherment, dataEncipherment

subjectAltName = @alt_names

[alt_names]

DNS.1 = localhost

IP.1 = 127.0.0.1Next, generate a key and certificate signing request for localhost. (I think I read that when asked for the “common name” for the cert, you should put a period at the end, to make it a fully-qualified domain name (FQDN), like so: “localhost.”). It worked for me.

The “days” parameter can’t be larger than 825 on macOS, so that’s what I put.

openssl genrsa -out localhost.key 2048

openssl req -new -key localhost.key -out localhost.csr

openssl x509 -req -in localhost.csr -CA myCA.pem -CAkey myCA.key -CAcreateserial -out localhost.crt -days 825 -sha256 -extfile localhost.extImport myCA.pem and localhost.crt into macOS Keychain Access.app

“Get Info” on both of them and trust them with “Always Trust”.

If ever you need a .pem file of the cert, just concat the .crt and .key like so:

cat localhost.crt localhost.key > localhost.pemWith these newly created and trusted certificates you can finally run Twisted again. Chrome will complain, but this time, you’ll be able to click through!

twistd -n web --path=. -c /Users/oelna/.certificates/localhost.crt -k /Users/oelna/.certificates/localhost.key --https=4433

Ich gebe zu, ich habe mir erst seit ein paar Stunden Gedanken darüber gemacht, aber als ich gelesen habe, wer gerade alles an der Technik zum digitalen Impfnachweis der Bundesregierung arbeitet, musste ich mir schon etwas an den Kopf greifen.

Das Bundesministerium für Gesundheit hat IBM, Ubirch, govdigital und Bechtle mit der Entwicklung einer Impfpass-App beauftragt.

Vor kurzem stand da noch mehr und genaueres, über wie viele Leute da beteiligt sind, aber mal ganz ehrlich: hätte da nicht auch ein Team von einer Hand voll Leute gereicht? Ist das nicht schon wieder Design by committee? Was ist denn überhaupt der Job?

Der digitale Impfnachweis wird in der Arztpraxis oder in einem Impfzentrum generiert. Nach Eingabe oder Übernahme der Daten wird ein 2D-Barcode erstellt, den die Nutzer direkt abscannen können oder auf einem Papierausdruck mitbekommen und später einscannen können.

Man muss also:

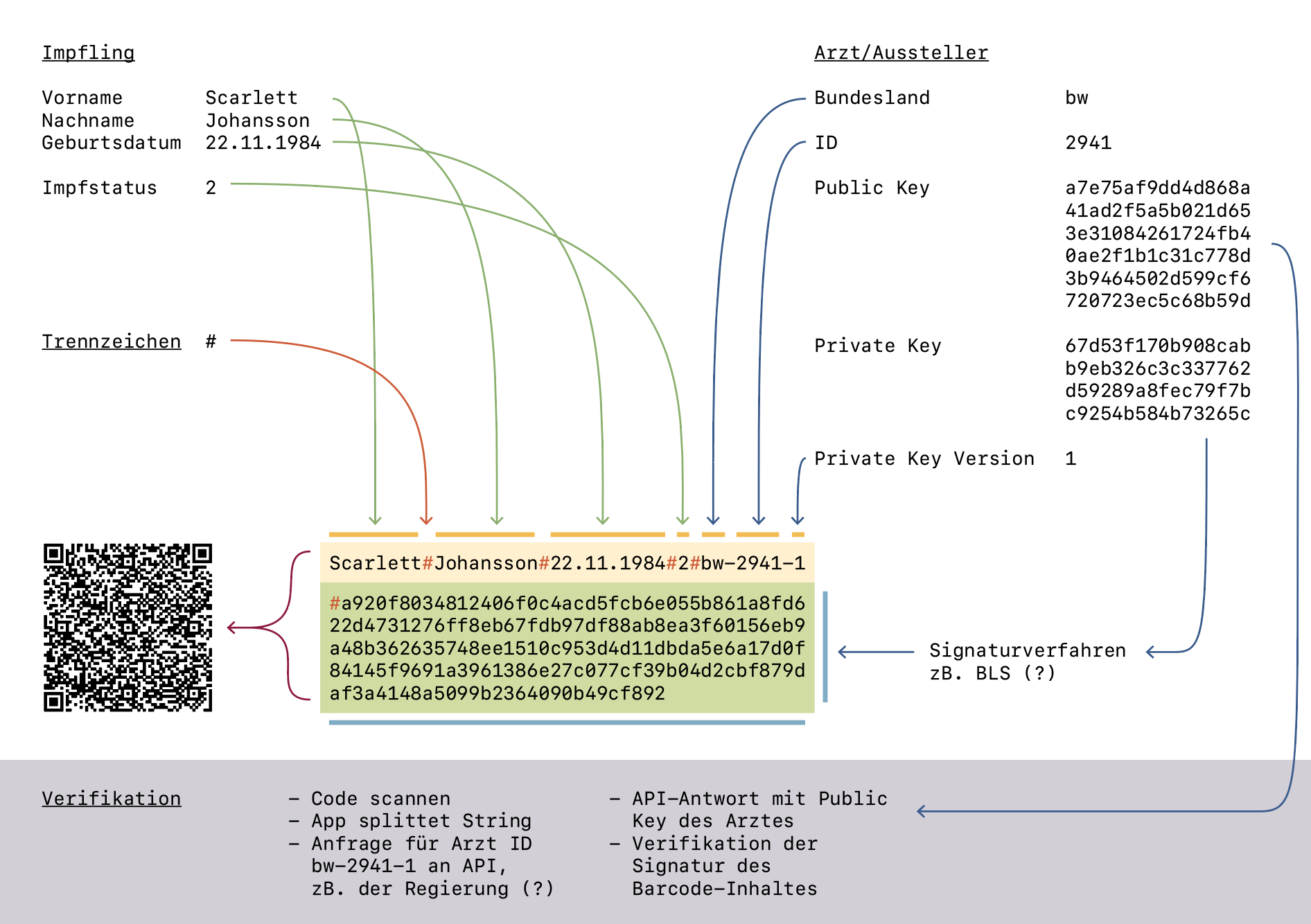

Ich denk, das ist es doch schon. Ich bin wirklich kein Profi, was Crypto-Sachen angeht, aber interessiere mich schon lang dafür. Nach kurzer Recherche stellt sich heraus, dass es mit quasi fertigen, anerkannten Mitteln, zB. BLS, recht einfach ist, eine kurze Signatur für einen Text zu erzeugen (oder mit Klassikern wie PGP eine lange Signatur?). Ist man dann nicht schon fertig, wenn man die benötigten Daten und die Signatur in einen Barcode packt? Ich hab das mal in einer Grafik zusammengebastelt, wie ich mir den Ablauf vorstelle.

Sicher, ganz so einfach ist es wahrscheinlich nicht, aber ich bin ja auch kein mehrköpfiges Team. Wenn man noch einrechnet, dass man eine kleine API zur Abfrage der Public Keys der Ärzte ganz Deutschlands braucht und vielleicht noch ein browserbasiertes Frontend basteln muss, das die Ärzte bedienen können, braucht man sicher eine Woche, bis es rund läuft. Ich bin kurz davor, das als Proof-of-concept schnell selber zu machen. Klingt doch spannend.

Wenn jemand wirklich was vom Thema versteht, freue ich mich über Kommentare. Ansonsten lehne ich mich jetzt zurück und beobachte, wie sich das Thema weiter entwickelt.

Natürlich konnte ich es nicht sein lassen: Demo des Projekts auf GitHub (Source)

This is mainly a list for myself and does not aspire to be complete or a reference to anybody other than myself.

PS: I also maintain a list of decent free sans-serif fonts for use in webdesign.